Science education

I’ve been engaged in public science education for most of my life. Even when in university I used to write articles for a student newspaper highlighting the research projects of pure mathematics professors called “Professays”.

I worked for 16 years for Greenpeace on energy and climate change, and then promoted a huge variety of science-based environmental campaigns on Greenpeace’s international website as the international “new media campaigner”.

Many of the well-educated people I know confuse astronomy and astrology, think that light-years and parsecs are both measures of time, and do not recognize the name “Sirius” unless it is a Harry Potter character.

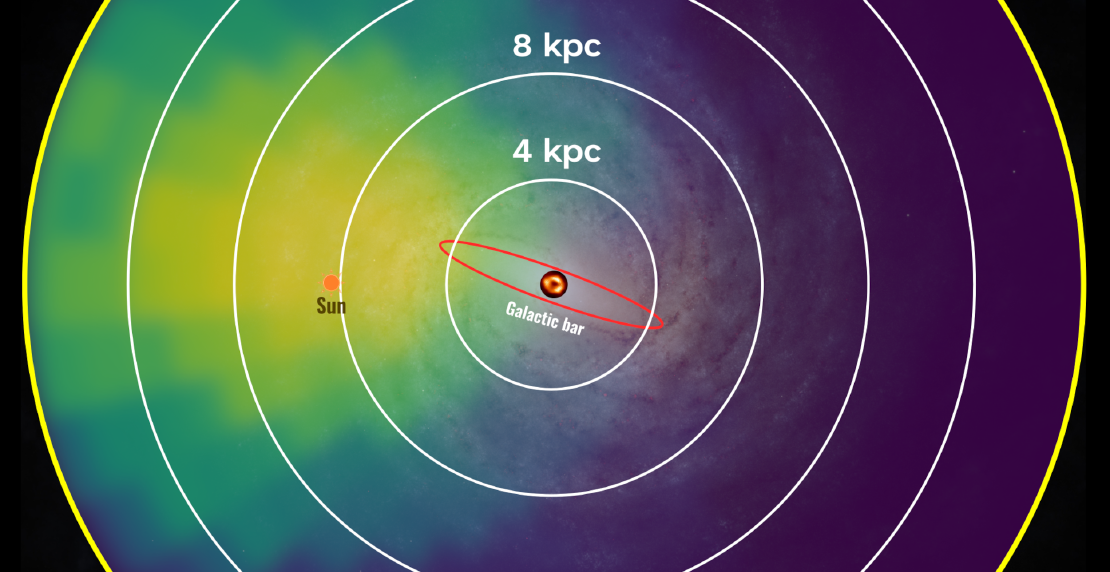

About 25 years ago, I started a website on galactic cartography, gathering together and interpreting the available research on the structure of the Milky Way. After the European Space Agency’s Gaia Mission launched in 2013, I was invited to volunteer with the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium as a galactic cartographer, making maps for public outreach around various Gaia data releases as well as other research papers.

Other than a small successful Kickstarter in 2018, almost all of my astronomy work, including the work I have done for the Gaia Mission, has been self-funded using income from a once lucrative career in web software development.

That has dried up for now and I have been looking into possible funding sources for my science education work. That turns out to be very hard.

Two recent Kickstarters have failed and the many astronomers I work with have no viable suggestions to fund astronomy public education.

Some of the maps and animations I have helped produce have received hundreds of thousands of views.

Generally speaking, when a professional astronomer does “public outreach” it means that they are trying to get journalists to write about one of their recent papers, with the hope that the column inches or TV clips will make it easier to get approval for their next research grant. Which is fair enough. Getting any science grant approved is always hard.

But in the mean time, many of the well-educated people I know confuse astronomy and astrology, think that light-years and parsecs are both measures of time, and do not recognize the name “Sirius” unless it is a Harry Potter character.

The public ignorance on astronomy is vast, which is why I have been using techniques in visualization and gamification to capture the public attention.

And it has worked. Some of the maps and animations I have helped produce have received hundreds of thousands of views .

And I am currently working on a board game, Acrux , based on a real map of the Milky Way, which I know has major potential for public education.

I’ve found that I’ve had the best astronomy conversations ever while playing Acrux with non-astronomers. People ask where the star names come from, the meaning of the temperature types, how we detect exoplanets, what the Gum nebula is …

This week I tried an experiment to attempt to raise 100 euros to print an new Acrux prototype. Even though I was asking for 5 euro donations from my thousands of social media followers, the cost of a Starbucks coffee, it was harder to reach than I had expected.

It was successful in the end so I am grateful for that support!

If anyone has grants to suggest for astronomy public education, you can contact me here .

Related Posts

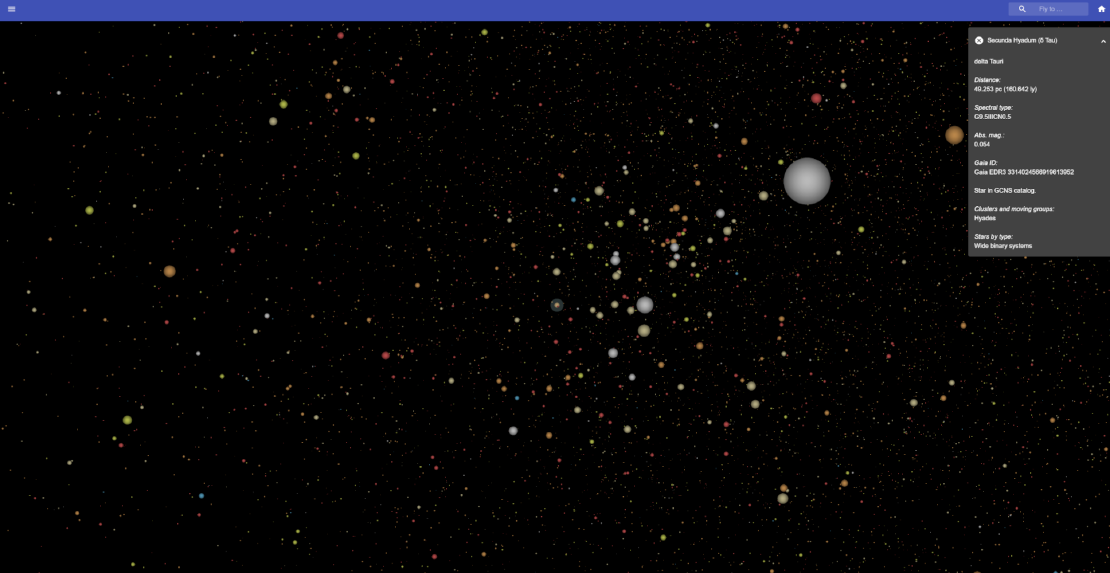

Flying through the nearby stars

Astronomer Richard Smart led a team a few years back to create the Gaia Catalog of Nearby Stars , a carefully analyzed star sample within 100 parsecs (325 light-years).

Read moreAcrux board game

There are about 3-5 thousand new board games published every year. A board game designer would need to have a very special game to rise above the crowd.

Read moreWhere is the Gaia data?

The European Space Agency’s Gaia Mission has provided distance estimates, magnitude, colour and other data for almost 2 billion stars, making it possible to map out the local galaxy in detail for the first time.

Read more