The Phantom Arm

The study of the inner galaxy has a surprisingly controversial history. How could Gaia DR4 help?

Island Universes

After examining images he had taken of a region of the Andromeda constellation in October 1923, Edwin Hubble wrote a letter to Harlow Shapley, the director of the Harvard Observatory. After receiving it, it is often told that Shapley turned to his graduate student Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin and said “Here is the letter that destroyed my universe.”

Using a Cepheid luminosity / distance relationship established by Harvard astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Hubble determined that Cepheid stars in the Andromeda nebula were located far beyond the Milky Way. The Andromeda nebula was its own island universe - a galaxy.

Here is the letter that destroyed my universe.

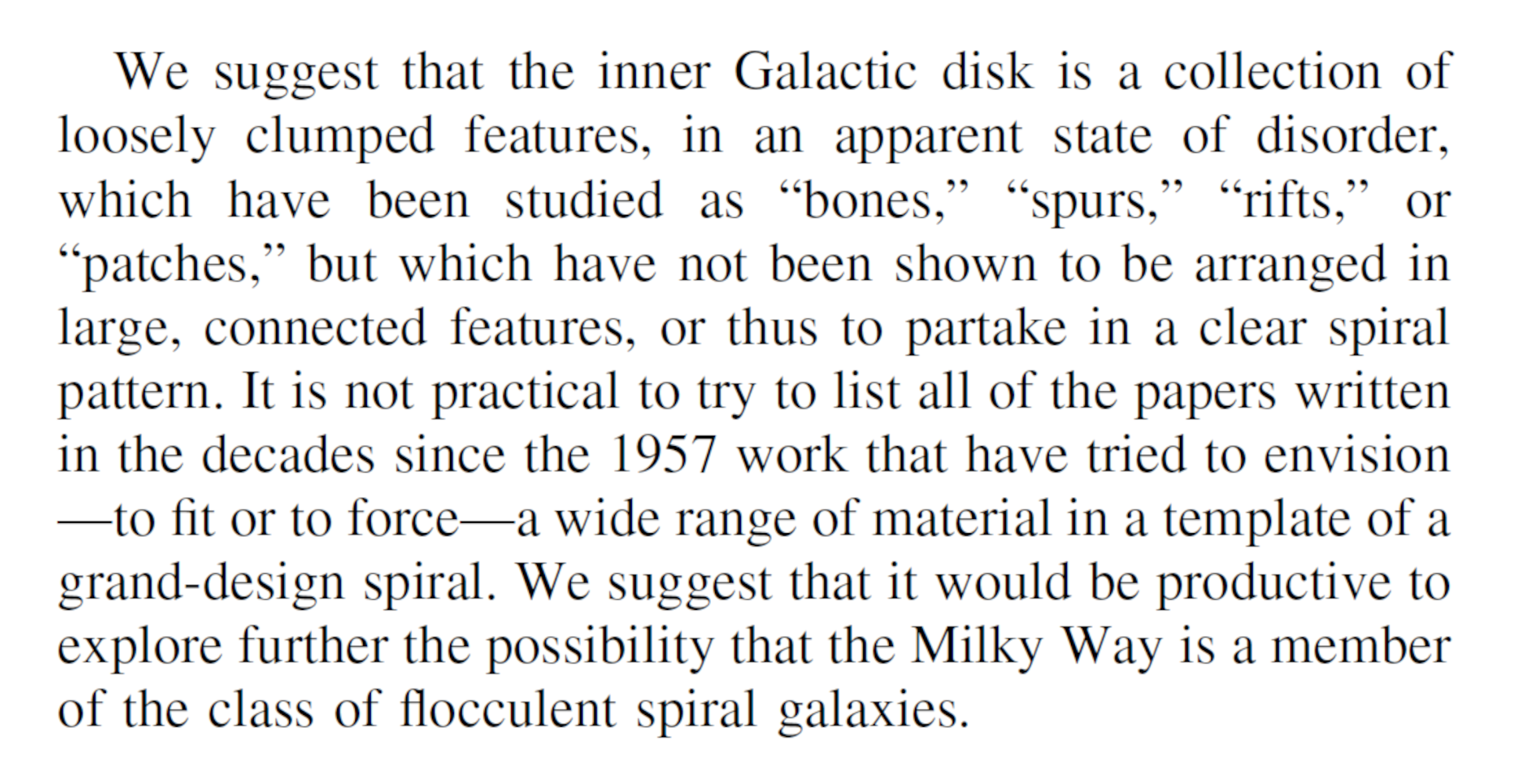

Following this crucial result, Hubble studied many of these galaxies and determined that most fell into two categories - elliptical galaxies, which were giant balls of stars, and disk galaxies, which were rotating thin structures. Most of the disk galaxies (but not all) had spiral arms - elongated structures that often vaguely resembled logarithmic spirals.

It was clear that the Milky Way must be a disk galaxy - but did it have spiral arms?

Because the Sun was immersed in a dusty region of the disk with limited views beyond, it was not clear that we would ever know. Astronomers studied the question for decades with no clear conclusions.

And then in 1951 there were several breakthroughs, starting a Golden Age in galactic cartography.

The Golden Age begins

In January 1951, Jason Nassau and William Morgan released a new catalog of highly luminous hot stars: “A Finding List of O and B Stars of High Luminosity”.

On March 25, 1951, Harold Ewen, working with his thesis advisor Edward Purcell at Harvard University, made the first successful detection of the 21-centimeter spectral line of neutral interstellar hydrogen, opening up the possibility to map the velocity of hydrogen gas throughout the galaxy.

On May 11, the Dutch radio engineer Christiaan Muller confirmed the detection using a repurposed German radar dish at the village of Kootwijk in the central Netherlands, followed in early July by Wilbur Christiansen and Jim Hindman in Australia. All three teams of radio astronomers would play major roles over the coming decades.

William Morgan, who to great excitement and a standing ovation, showed the first map of galactic structure - parts of the Perseus and Local arms …

In December 1951, Jan Oort, the director of the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands and one of the world’s most renowned astronomers, arrived in Cleveland to give the annual Henry Norris Russell lecture before the American Astronomical Society winter meeting.

The day before his address, Oort introduced William Morgan, who to great excitement and a standing ovation, showed the first map of galactic structure - parts of the Perseus and Local arms - using a slide of a model of OB star concentrations made out of cotton balls.

During his address the following day, Oort gave more details on some of the OB stars on Morgan’s map, explaining that they formed the cores of young star formation regions. He want on to describe the importance of the detection of the 21 cm line and predicted that radio astronomy would map the entire galaxy, far beyond the obscuring dust of the local region.

And so the Golden Age began with excitement and great optimism.

The inner galaxy

Morgan’s original model only had a single cotton ball representing an OB concentration in the inner galaxy.

In a 1952 paper, Morgan, Sharpless and Osterbrock noted: “There is some evidence for another arm located at a distance of around 1500 parsecs in the direction toward the galactic center. This is defined by the series of condensations of O and B stars from galactic longitude 253° in Carina to 345°, the small cloud in Sagittarius. The data are so fragmentary, however, that more observations from the southern hemisphere will be necessary before a definite conclusion can be reached.” In modern galactic coordinates, this inner arm would stretch from 285° in Carina to 20° in Sagittarius and is the first reference to what would later be called the Sagittarius-Carina arm.

Are astronomers mapping the “irregular parts” or the “characteristic spiral pattern”?

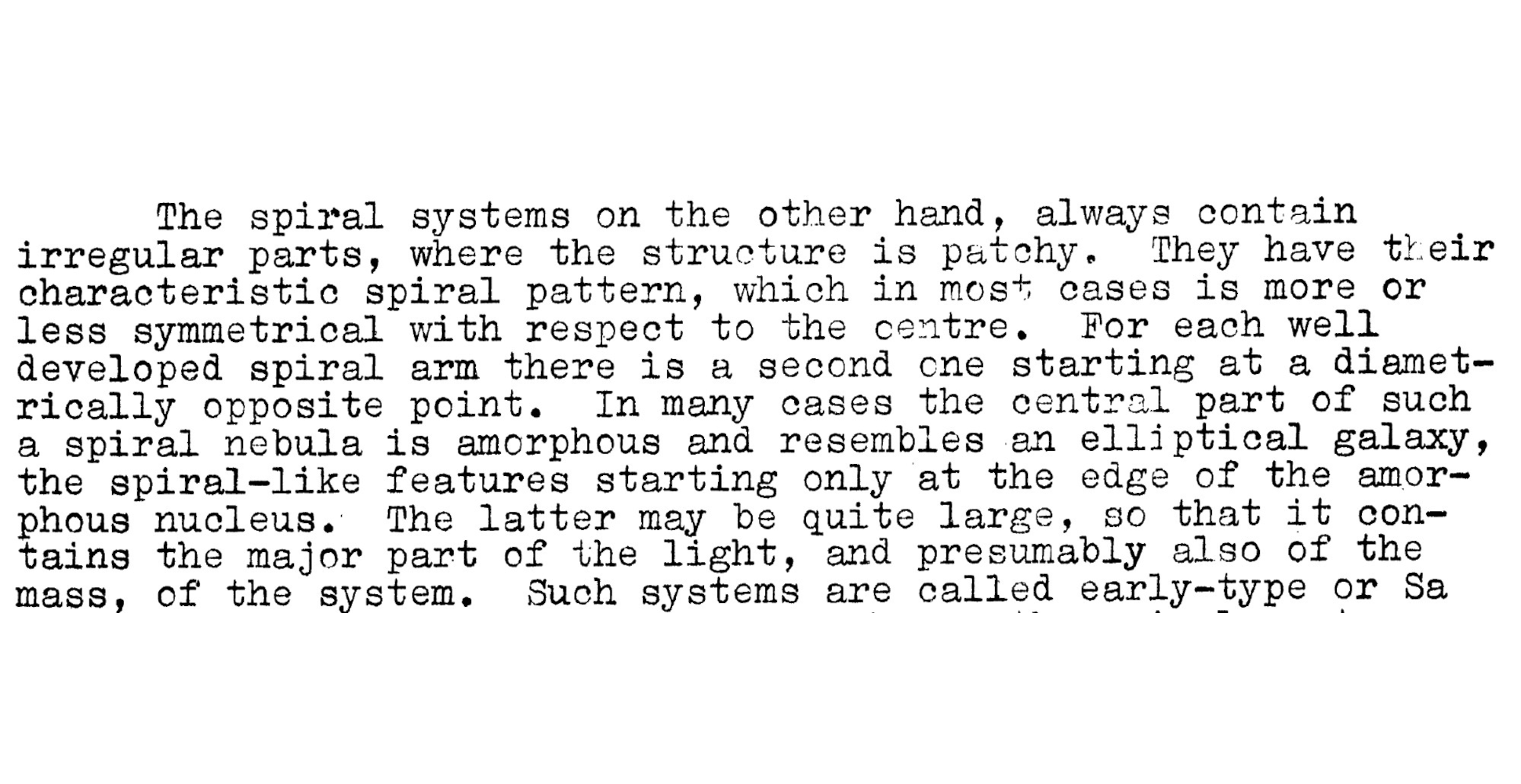

Also in 1952, Oort and Muller published a paper which set out concepts and questions that have haunted galactic cartography ever since.

Are astronomers mapping the “irregular parts” or the “characteristic spiral pattern”? What do we mean by “amorphous nucleus”? Oort mentions that it can be quite large. How large? Could it be, for example, as large as the entire inner galaxy?

The Kwee segments

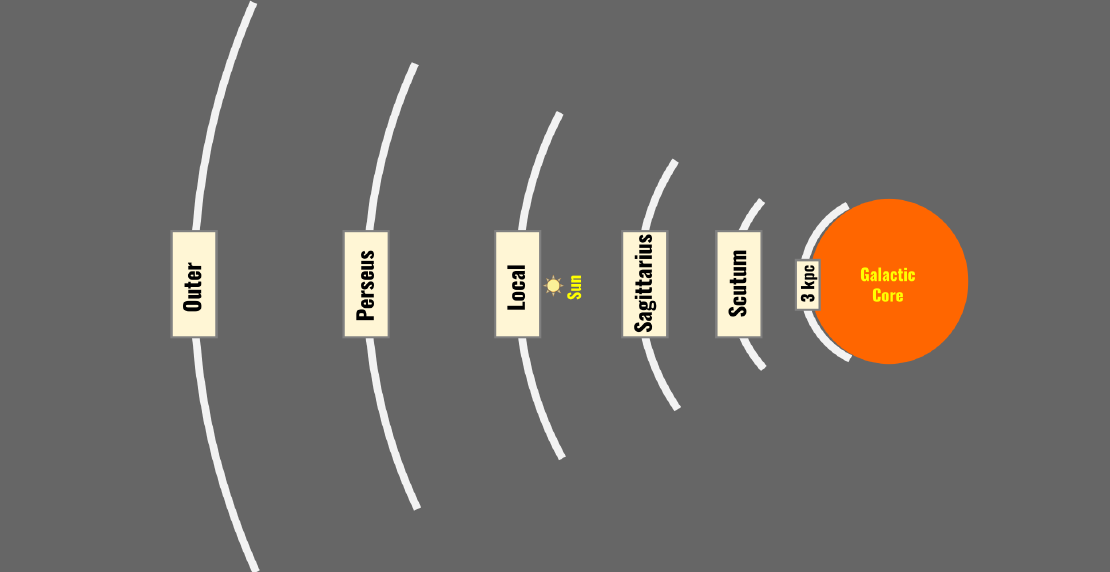

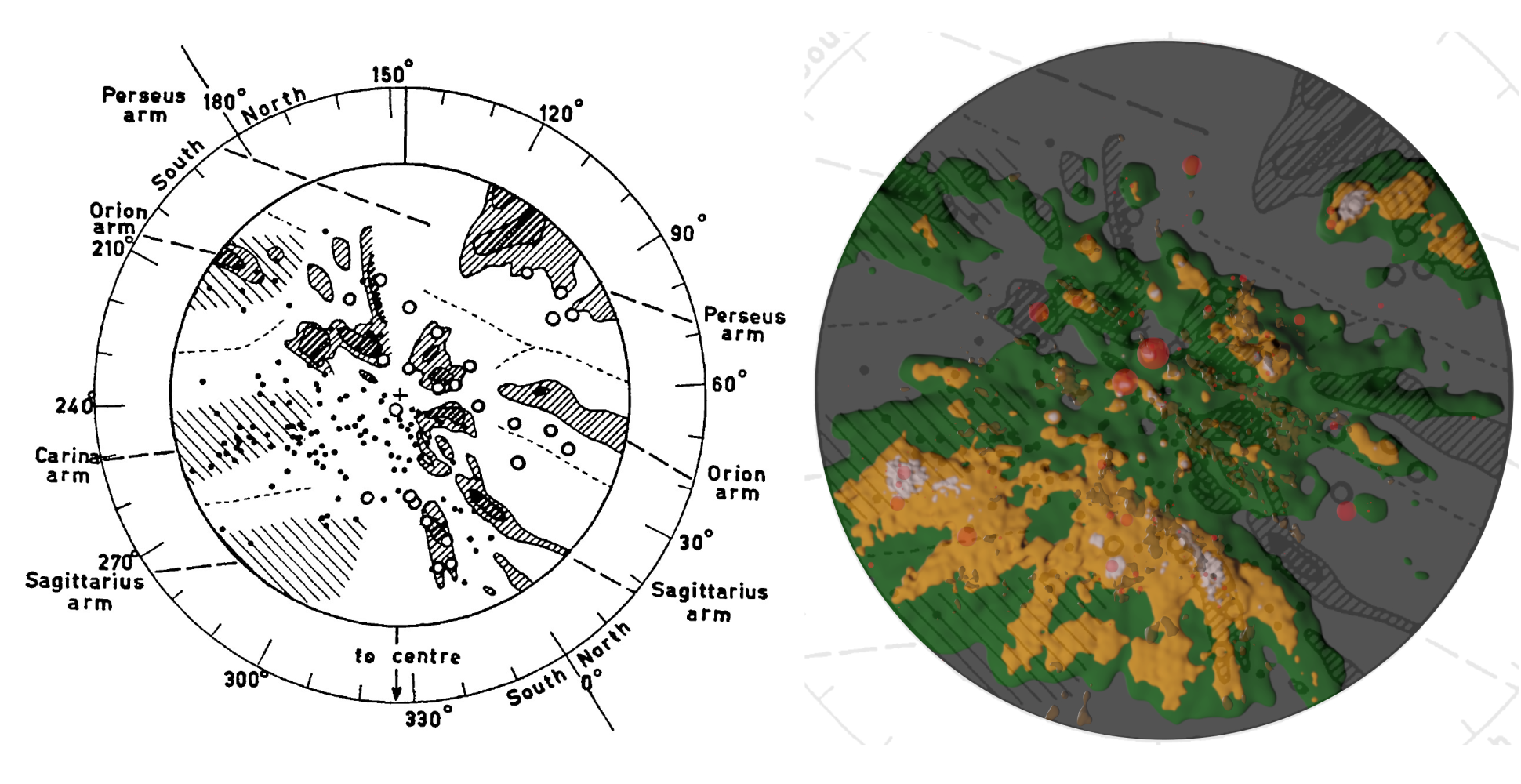

The Dutch radio astronomers published two major papers in 1954. The first, from Van de Hulst, Muller and Oort was mostly about the outer galaxy, so I’ll leave a detailed discussion for a future article. However, it did make some influential naming suggestions: the Orion arm for “the arm passing through the Sun” and the Sagittarius arm for “the first arm encountered when proceeding in the direction of the centre”.

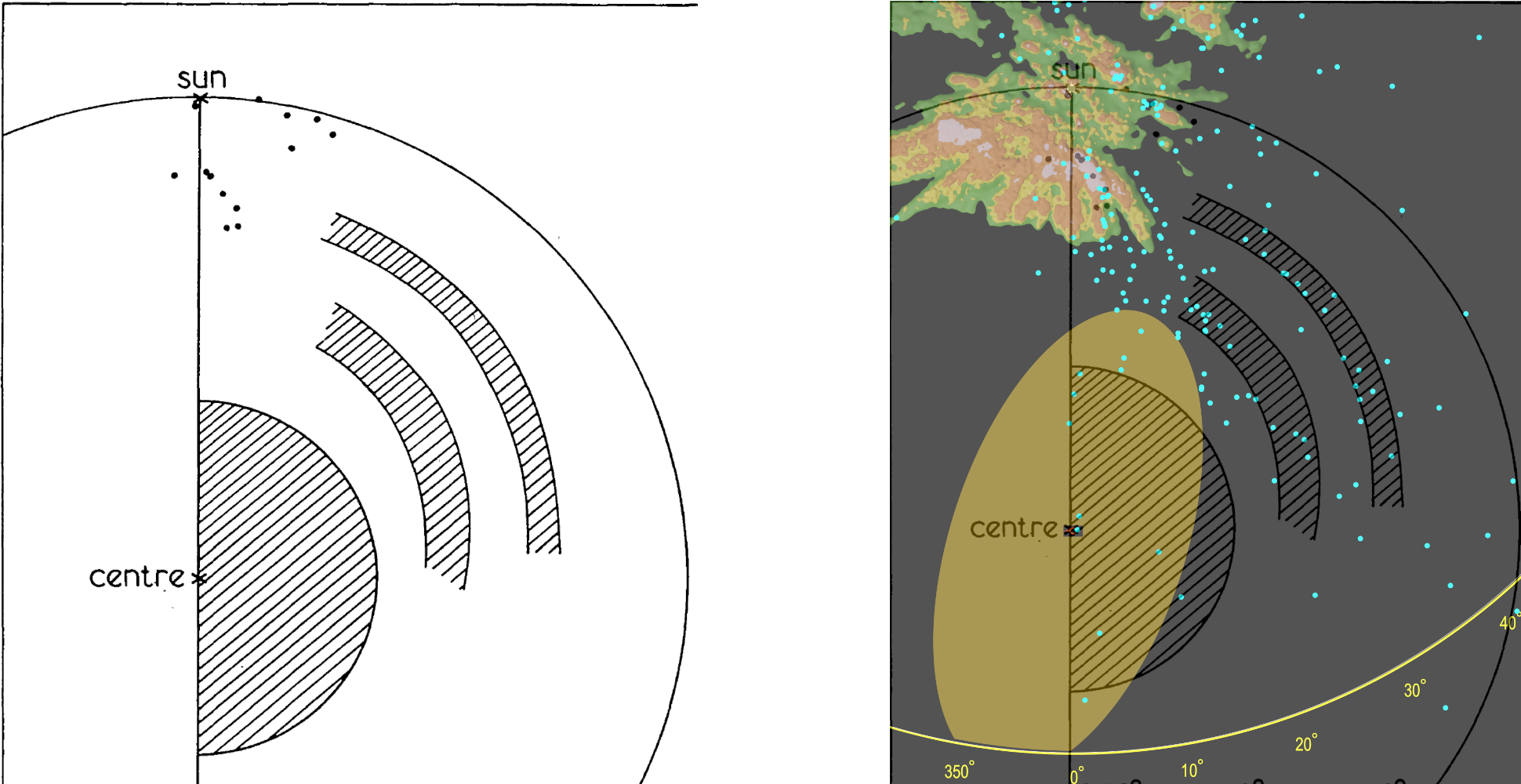

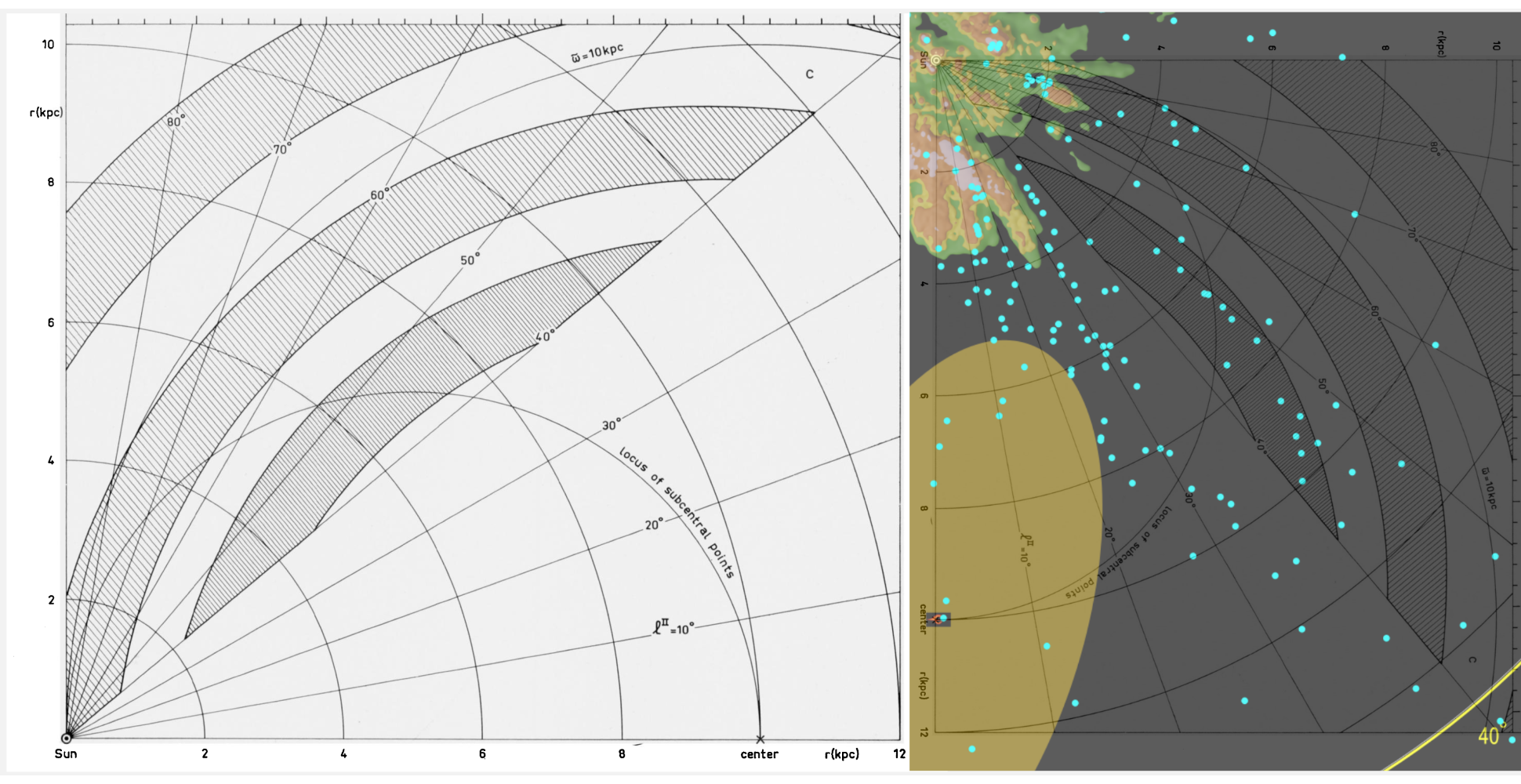

The paper described two spiral segments in the first quadrant of the inner galaxy.

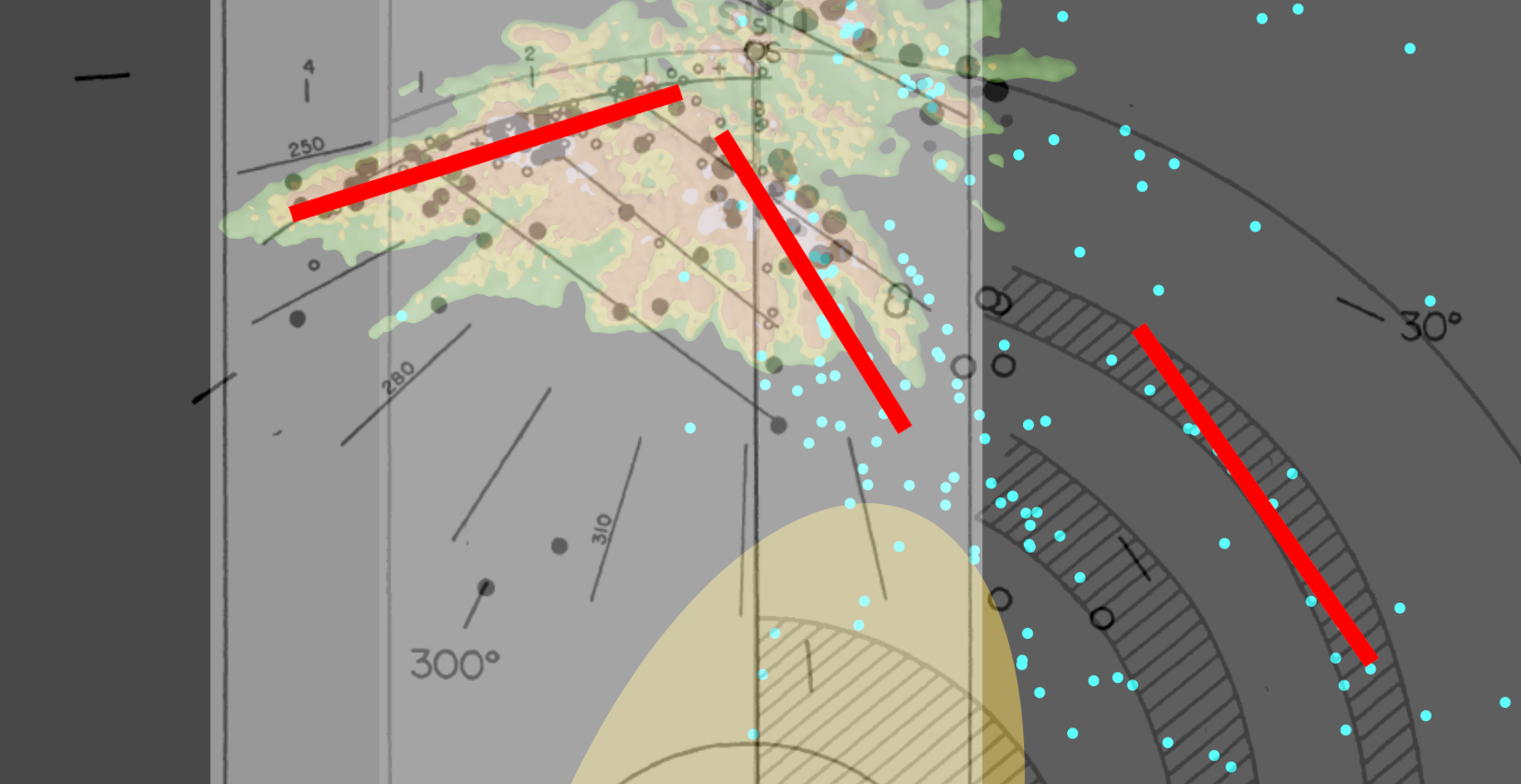

The second paper, from Kwee, Muller and Westerhout, reported on what turned out to be a major discovery about the galaxy in the dusty and obscured first quadrant. The paper described two spiral segments in the first quadrant of the inner galaxy. In the image below I show Figure 8 from this paper compared to an overlay on the most recent maser and Gaia DR3 data. It is immediately apparent that the masers line up well with these segments, especially with the outer segment. The paper also suggests that the outer segment may be a “continuation” of a spiral structure suggested by concentrations of OB stars in the inner galaxy.

Completing the OB picture

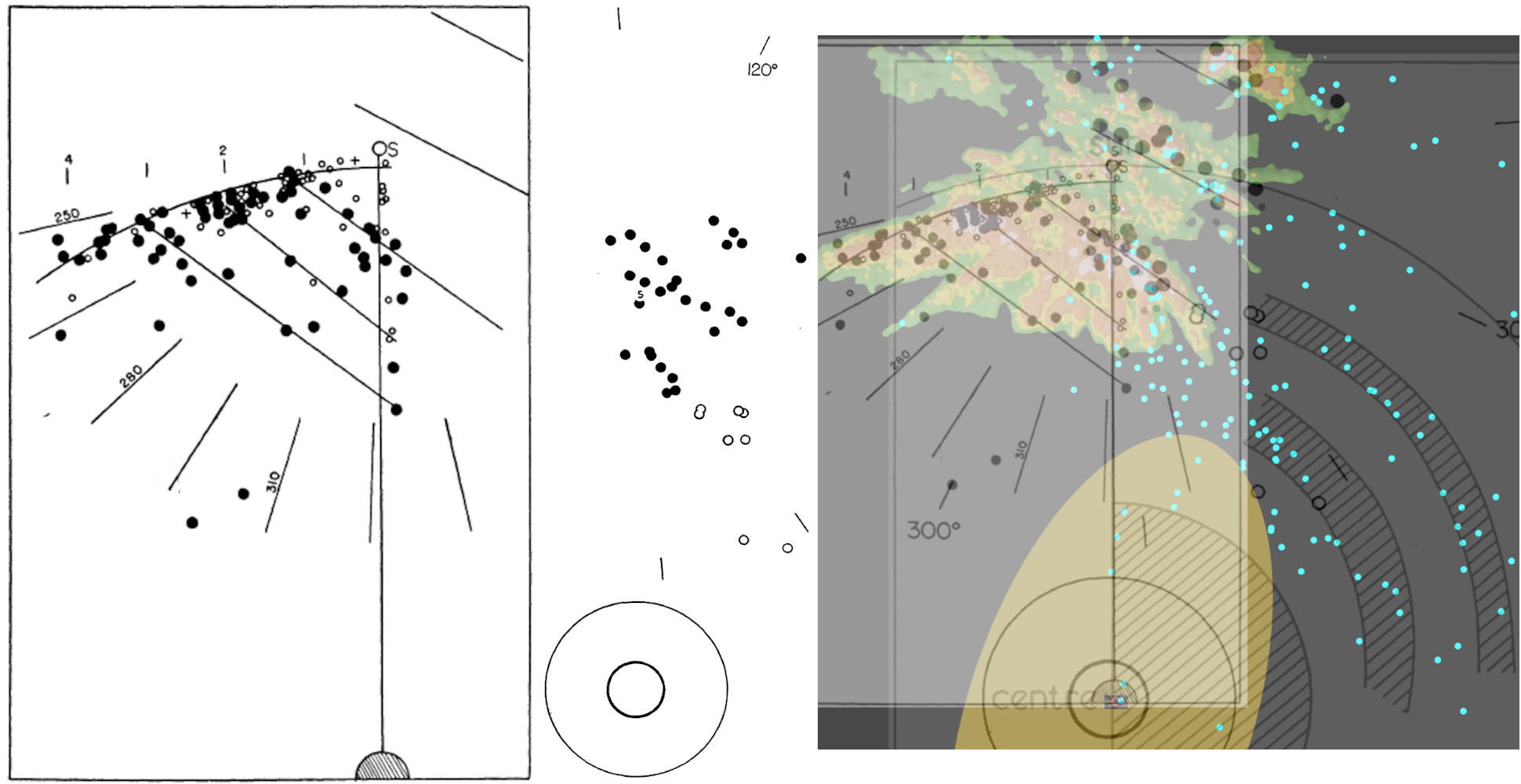

In 1953, Morgan, Whitford and Code published a revised map of OB star concentrations, but only for stars visible in the northern hemisphere. In 1956, Dorrit Hoffleit completed the OB picture with a map of OB star concentrations visible from South Africa.

This image shows the Hoffleit and Morgan maps and then a map overlaying both OB maps and the Kwee segments on top of maser and Gaia DR3 data. As you can see, the 1950s and modern data look very compatible.

Morgan split his Sagittarius OB stars into near (black dots) and far (white dots), creating an ambiguous orientation for this spiral segment. Including the far stars suggested that the segment was oriented towards the centre of the galaxy. Removing the far stars allowed the possibility that the orientation might be parallel to the Perseus and Local arms Morgan had previously identified and towards the Kwee outer segment. The debate on the orientation of the Sagittarius region would re-emerge decades later.

Including the far stars suggested that the segment was oriented towards the centre of the galaxy.

Hoffleit speculated on the relation of the Carina arm to the rest of the galaxy - a debate that would continue throughout the Golden Age: “The new observations presented here might be looked upon as indicating the extension of [Morgan’s Sagittarius region] toward Carina. But, in view of the suspected uncertainty in the adopted absolute magnitudes and the fragmentary nature of the material for the greater longitudes, it is still unwise to present conclusions on the structure of the spiral arms in this quadrant as definitive.”

Schmidt adds a segment

In 1957, Maarten Schmidt published additional radio observations that he argued extended the outer Kwee segment around to the far side of the galaxy: “Spiral structure in the inner parts of the Galactic System derived from the hydrogen emission at 21-cm wavelength”. He combined the OB stars in Sagittarius with the Kwee outer segment and his new far segment to form one long “Sagittarius arm”.

The Van de Hulst and combined hydrogen maps

In 1958, Hendrick van de Hulst combined data from OB associations, Cepheids and atomic hydrogen out to 3 kpc to produce the most detailed map of the local galaxy yet published. The Van De Hulst map was remarkably similar (although of course less detailed) to maps produced from Gaia data today. There does seem to be a scaling issue in the second quadrant.

The map focused on what Oort earlier called the “irregular parts” of the galaxy with an outer area that attempted to provide some hints for Oort’s “characteristic spiral pattern”.

Van de Hulst commented ambiguously in the paper that “The more confused situation in the southern sky [inner galaxy] is not due solely to incompleteness of the observations.”

The more confused situation in the southern sky [inner galaxy] is not due solely to incompleteness of the observations.

Also in 1958, Oort, Kerr and Westerhout published their famous contour map combining hydrogen data from Dutch and Australian astronomers. I’ll look at that in another article.

The Stromlo map

In 1959, the director of Australia’s Stromo Observatory, Bart Bok, stepped into the discussion with a map produced with the help of Stromlo astronomer Jane Basinski.

Bok published the map mostly to argue the case that the Carina region connected to the Local arm, and that this Cygnus-Carina arm formed a major part of the local galaxy. Several other Australian astronomers studying the Carina region including Frank Kerr agreed with Bok and Golden Age cartographers were divided into groups that advocated a Cygnus-Carina arm, a Sagittarius-Carina arm or thought that Carina was a separate region.

The end of the Golden Age

Historical periods are inevitably arbitrary. But the Golden Age of galactic cartography can perhaps be ended by events that took place in 1969-1971.

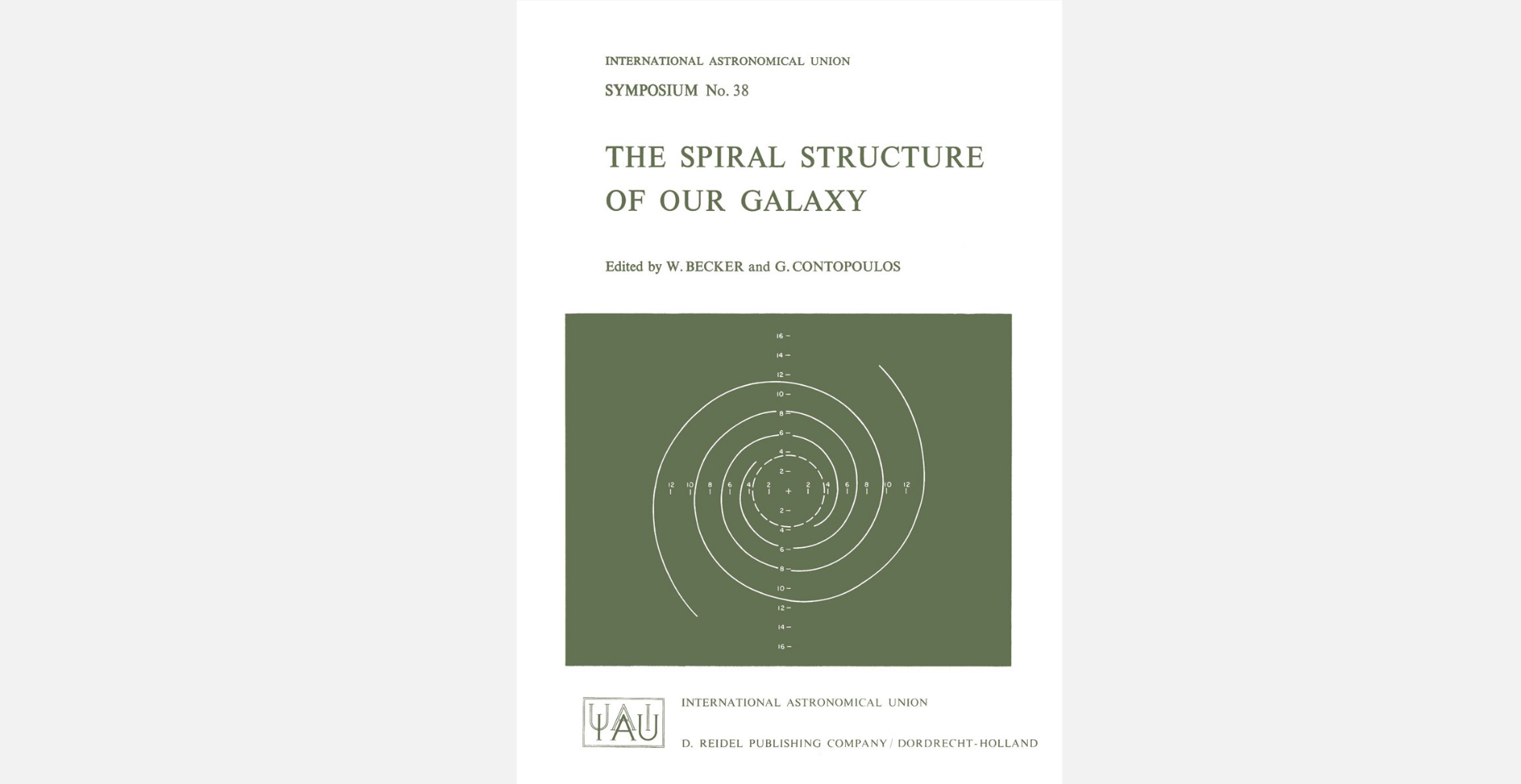

The first was a large IAU symposium, “The Spiral Structure of Our Galaxy” that took place in Basel, Switzerland from August 29 - September 4, 1969. It gathered almost all of the major figures to present papers that were ultimately published in a large book summarizing all that had been learned during the previous two decades.

As it became clear that “the symposium revealed considerable disagreement over several important problems”, some of the major figures gathered at the University of Maryland on February 16 and 17, 1970 to analyze their differences. Most were astronomers working in the US, although W.B. Burton attended to represent the Dutch astronomers. Bart Bok and Frank Kerr, the Australian astronomers, and Gart Westerhout, the Dutch astronomer, attended as they were all now working in the United States.

It is in the inner regions of the Galaxy that important discrepancies appear …

The Maryland event was an “unconference” with no papers presented, only discussion. According to the meeting minutes:

“Westerhout pointed out the spatial irregularies one encounters in trying to follow features in the l, V [radio velocity] diagram. He, together with Kerr and Weaver, stressed that the features we call spiral arms when observed with high resolution are turning out to be irregular spurs and pieces of arms that cannot be followed for more than a few degrees.” Oort’s dream of mapping both the “irregular parts” and the “characteristic spiral pattern” of the Milky Way seemed to have failed. The better the Golden Age cartographers were able to map the “irregular parts” the less success they seemed to have tracking the “characteristic spiral pattern”.

The Sagittarius arm as plotted does not closely resemble a spiral …

The final event that closed the Golden Age was the publication of a series of papers that examined the distribution of neutral hydrogen in the first quadrant by Burton and Shane. Previous papers on this topic from Kwee and Schmidt had used a repurposed German radar dish. Now the astronomers had access to more sophisticated radio telescopes that could produce more detailed data. Burton’s observations were able to confirm the Kwee outer segment but cast doubt on Schmidt’s grander Sagittarius arm. When mapping that region Burton and Shane noted “The Sagittarius arm as plotted does not closely resemble a spiral, the far branch being almost circular and the near banch quite sharply inclined.” This conclusion fit the general story of the Golden Age - the more data collected, the less clear the spiral structure became.

By the 1970s, Bart Bok’s beloved wife and fellow astronomer Priscilla Fairfield Bok was sliding into dementia, but as is often the case, she still had moments of clarity. One day, while sitting in their living room, she said “Bart, get out of spiral structure. The future is in star formation.”

The age of optimism was over.

There was one sentence in the Maryland unconference minutes that provided a possible hint for the future:

“It is in the inner regions of the Galaxy that important discrepancies appear and these are mainly related to the interpretation of tangential points of spiral features and the connections between them.”

Triumph of the race track

Vaguely lurking behind Oort’s concept of “characteristic spiral pattern” was the hope that the Milky Way would turn out to have a simple spiral structure - if not a grand spiral design then something close to it. Implicit to this concept of simplicity was the expectation that the spiral structure would consist of concentric spiral segments made out of fragments of logarithmic spirals. This goes back to Oort’s definition of the Sagittarius arm as “the first arm encountered when proceeding in the direction of the centre”. This made an assumption that there there would be a spiral arm that wrapped around the centre to be given this name instead of, for example, one or more arms that made sharp inclines such as Bok’s Cygnus-Carina arm, or a ring, or just flocculent random gas.

The mental model seems to be like a race track.

Real spiral arms are complex and chaotic 3D structures, not simple logarithmic curve segments, and the Golden Age cartographers were well aware of this. But somehow as the Golden Age faded into a sort of cartographic dark age with only a few astronomers working on spiral structure, that seems to have been forgotten or less valued. Instead of searching for a “characteristic spiral pattern”, astronomers simply assumed that there was one, and developed simple mathematical tools to determine whether that pattern had 2 arms or 4 arms.

Real spiral arms are complex and chaotic 3D structures, not simple logarithmic curve segments …

Remarkably, the cover of the proceedings for the 1969 Basel symposium showed such a race track model even though it did not appear to resemble any figure from a published paper from a major Golden Age cartographer. The cover appears to show what many of the assembled astronomers would have liked the structure of the Milky Way to be rather than anything closely resembling real data.

There is not even a Local arm on the 1976 map …

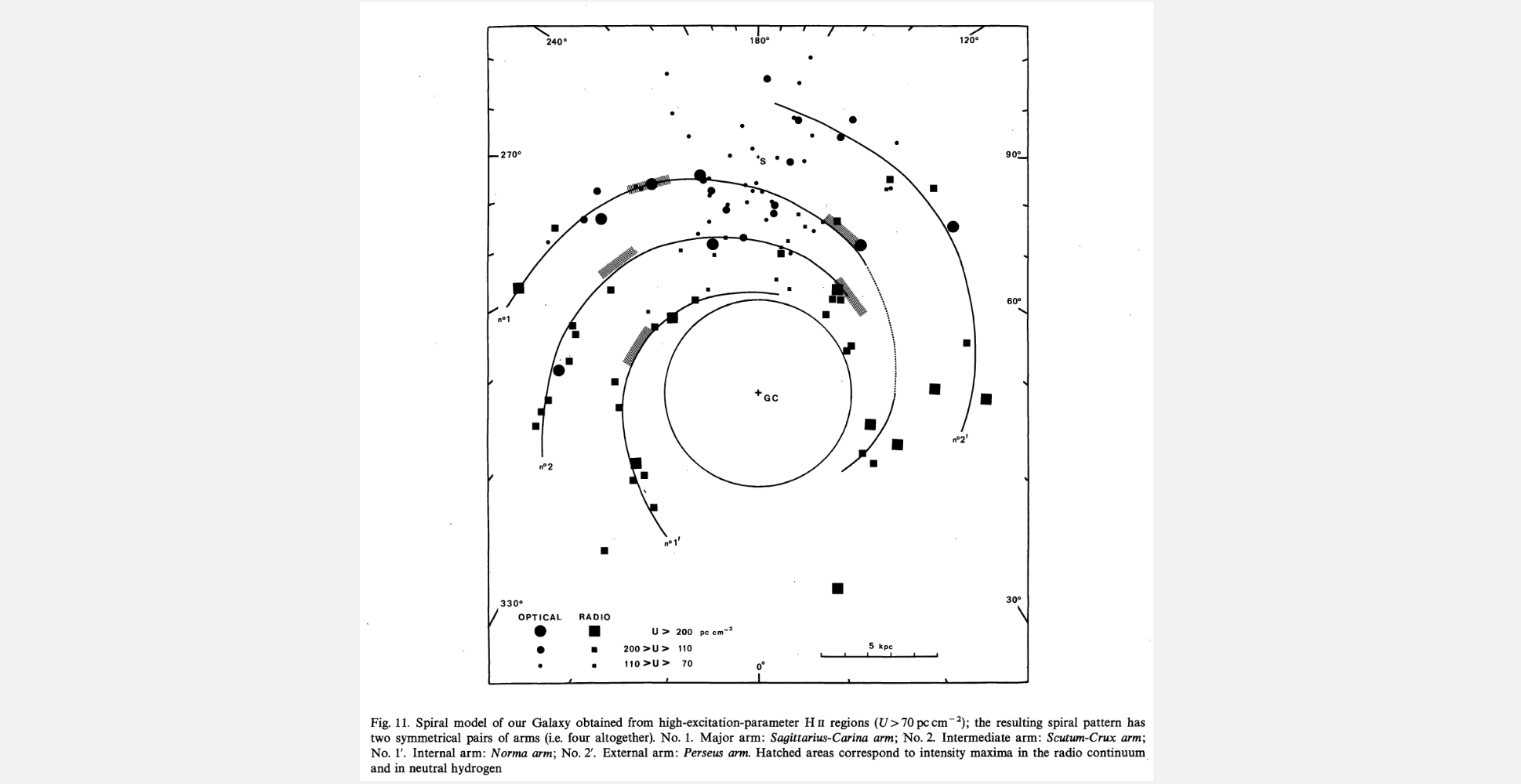

I’m a big fan of Georglin and Georgelin’s work on HII regions, but unfortunately their 1976 paper “The spiral structure of our Galaxy determined from H II regions” is another good example of race track cartography. The paper uses error prone kinematic distances to estimate distances to a (very useful) catalog of HII regions and then threaded 4 logarithmic spiral segments through some of them. One of these was a long Sagittarius-Carina arm that wrapped around the galactic centre. There is not even a Local arm on the 1976 map despite it appearing prominently in all the Golden Age maps because it would complicate the simple spiral pattern.

George Box, the British statistician, is supposed to have said “All models are wrong but some are useful” and of course this is true. The universe is a messy place. Models like Newtonian physics or the Bohr atom are known to be less accurate than more recent models but their simplicity and usefulness for practical calculations means that they are still taught in the class room.

So it is not always the case that scientists should choose models that best resemble real data. Usefulness is also an important consideration.

But how useful are the race track models?

In any case they became very popular. For more than 30 years - an entire generation - astronomy students were shown simple spiral models made out of logarithmic curve segments. NASA, ESA and other space agencies used these models to create highly speculative images of the Milky Way. Astronomers debated tangent points and orientations but rarely whether these models were appropriate to describe a real galaxy.

Infrared objections

In 2009, a team of infrared astronomers led by Edward Churchwell reported on observations of the Spitzer space telescope in the paper “The Spitzer/GLIMPSE Surveys: A New View of the Milky Way”. They observed increases in infrared star counts at the tangencies to two spiral arms, but “there is no detectable increase in the star count where the Sagittarius arm is expected to lie”. The same team had previously put out a press release with the title “Two of the Milky Way’s Spiral Arms Go Missing”. In the press release, Robert Benjamin argued that the Sagittarius and Norma/Outer structures must be minor arms of the Milky Way because they could not be detected in infrared.

Two of the Milky Way’s Spiral Arms Go Missing

The Spitzer team released an image of the Milky Way which, while still heavily influenced by race track models of the Milky Way, introduced a number of features from real Milky Way observations including a galactic bar and two major spiral arms. NASA artist Robert Hurt’s illustrations of HII regions and OB star associations resembled those seen in real galaxies. As a result the Hurt image was praised as the best full image of the Milky Way ever produced and in the following years was widely used in scientific papers and media stories.

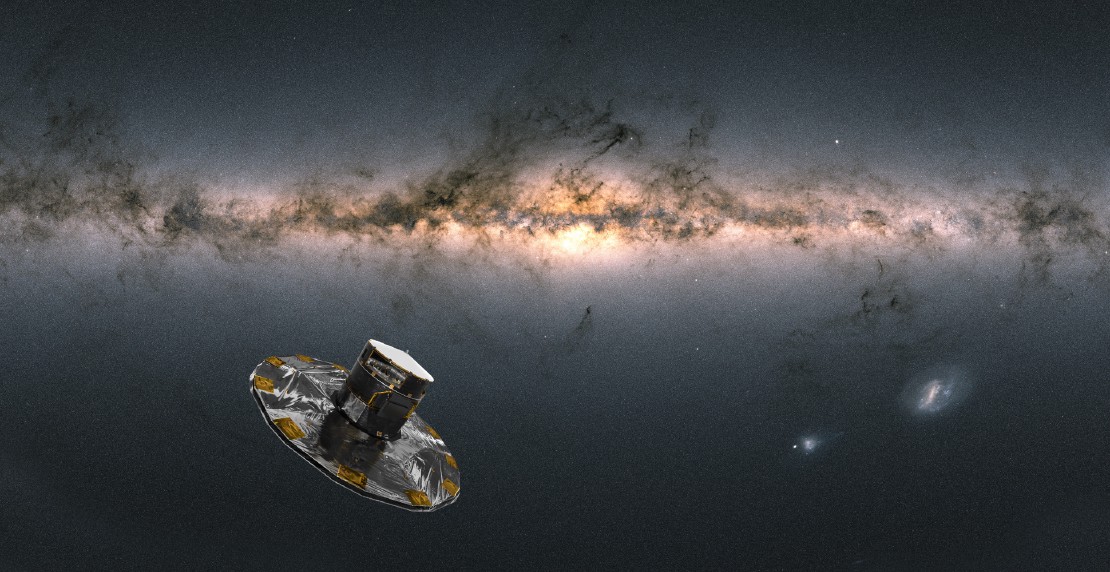

The Age of Astrometry

In 2010, radio astronomers launched the BeSSeL survey to measure parallaxes for masers visible in the northern hemisphere. Three years later the Gaia spacecraft launched from the European Space Agency’s space port in French Guiana. The BeSSeL and Gaia surveys created a revolution in astronomy by accurately measuring incredibly small shifts in object positions as the Earth orbits the Sun. The angle of these shifts, called parallax, enabled distance estimates that were much more reliable than the photometric and kinematic estimates used by Golden Age astronomers.

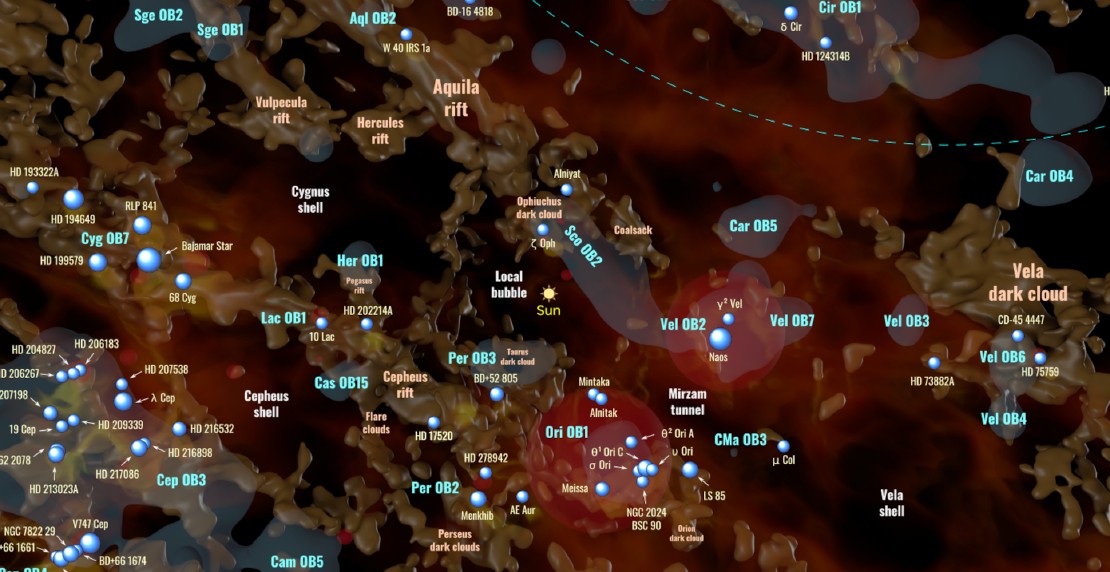

For various reasons this new Age of Astrometry has not yet allowed the determination of Oort’s “characteristic spiral pattern” but has certainly provided far more detail on what Oort called the “irregular parts” of the galaxy.

A Sagittarius spur?

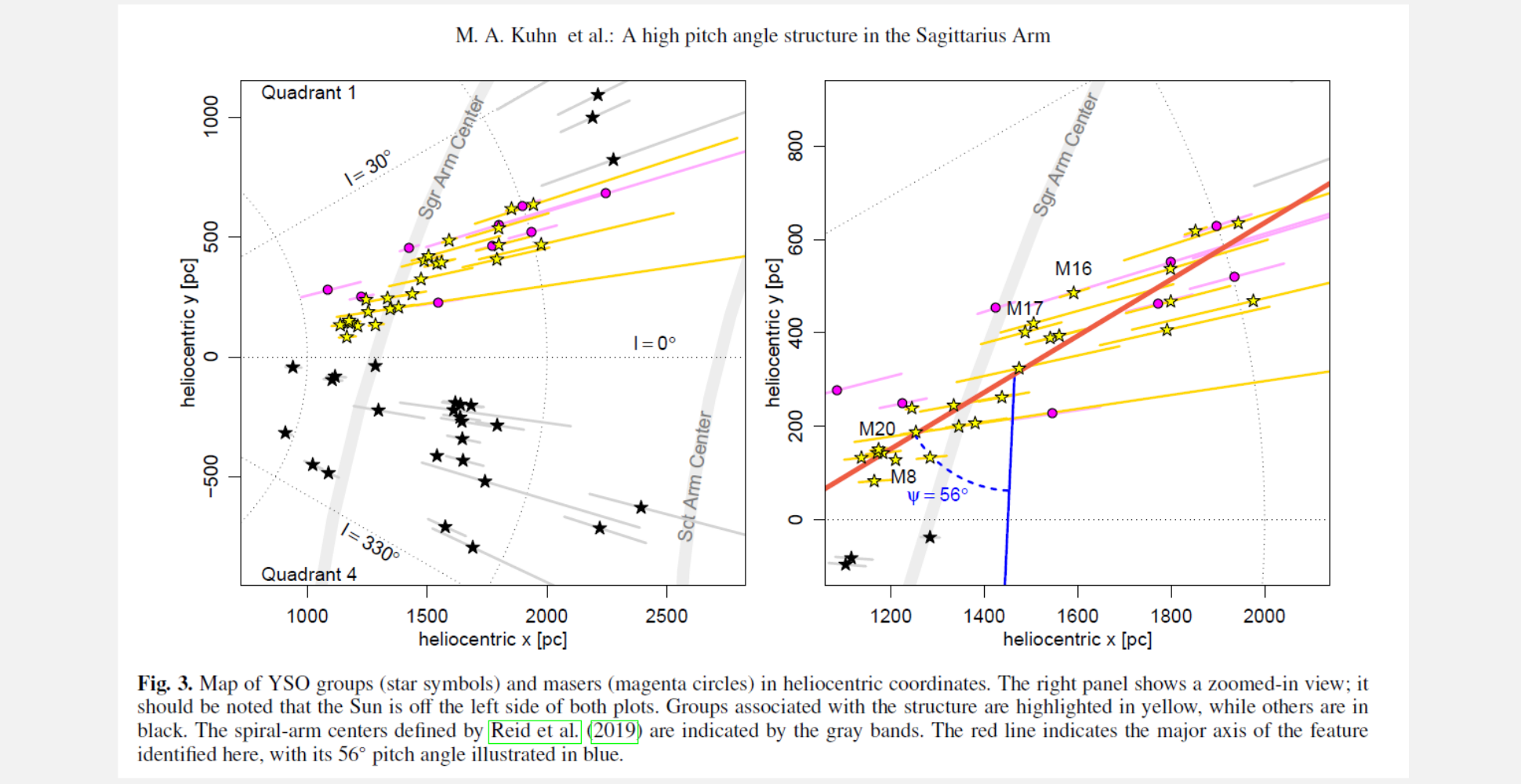

In 2021, a group of astronomers with lead author Michael Kuhn sent a letter to the editor of the Astronomy and Astrophysics titled “A high pitch angle structure in the Sagittarius Arm”. The letter points out that young stellar groups and masers connected to the Sagittarius OB associations do not share the traditional orientation of the Sagittarius arm, but rather run at a sharp angle to it. The orientation in fact appears to point towards the end of the galactic bar.

In fact, this same orientation could be seen in the Sagittarius OB star concentrations mapped by Morgan, Whitford and Code in 1953. More generally, the various segments often stitched together to form a Sagittarius-Carina arm have significant gaps and differences in orientation as can be seen in this version of the image I displayed above.

The authors of the 2021 letter did not take a clear position on the significance of the observed high pitch angle, noting that it might be an inter-arm spur or a mass concentration in the Sagittarius arm.

They did not address a larger question: does the Sagittarius arm actually exist?

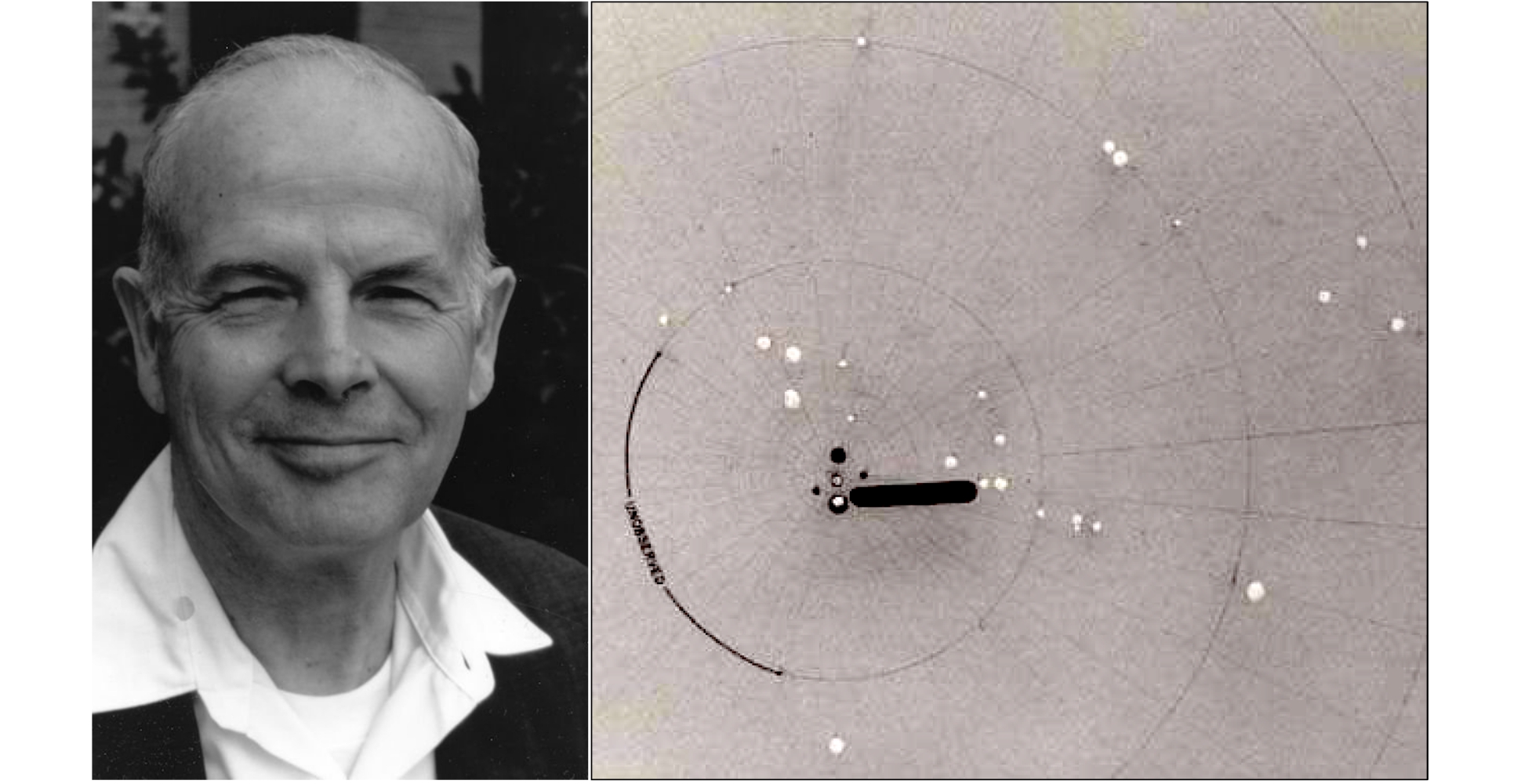

Burton takes a stand

Perhaps no astronomer knows more about the evidence for a Sagittarius arm than the famously cautious and meticulous Golden Age radio astronomer W. B. (William Butler) Burton. Not only did he map the first quadrant in the early 1970s, but his 1970 PhD dissertation was on the Sagittarius arm: “The Sagittarius spiral arm and the general distribution of Hydrogen between 0 deg and 90 deg longitude. Streaming and geometrical effects on the derivation of density”.

Burton is now in his 80s but the availability of a major new neutral hydrogen data set, HI4PI (released in 2016), convinced him to write a new 2025 paper with American radio astronomer Dana S. Balser: “The Flocculent Structure of the Inner Milky Way Disk”.

Burton briefly criticised recent work on spiral structure:

“Yet much of that subsequent work seems to have been aimed at mapping the spiral structure of the Milky Way that was presupposed to be characterized by a grand-design pattern, with, for example, measurable tilt angles of logarithmic spirals of a measurable number wrapping over large angles of Galactocentric azimuth.”

In case his meaning was not clear, Burton footnoted the word “presupposed”:

The dictionary definition of “presupposed” seems relevant to what motivated many efforts to determine the global morphology of the Milky Way: “…tacitly assume at the beginning of a line of argument or course of action that something is the case” (OED, n.d.)."

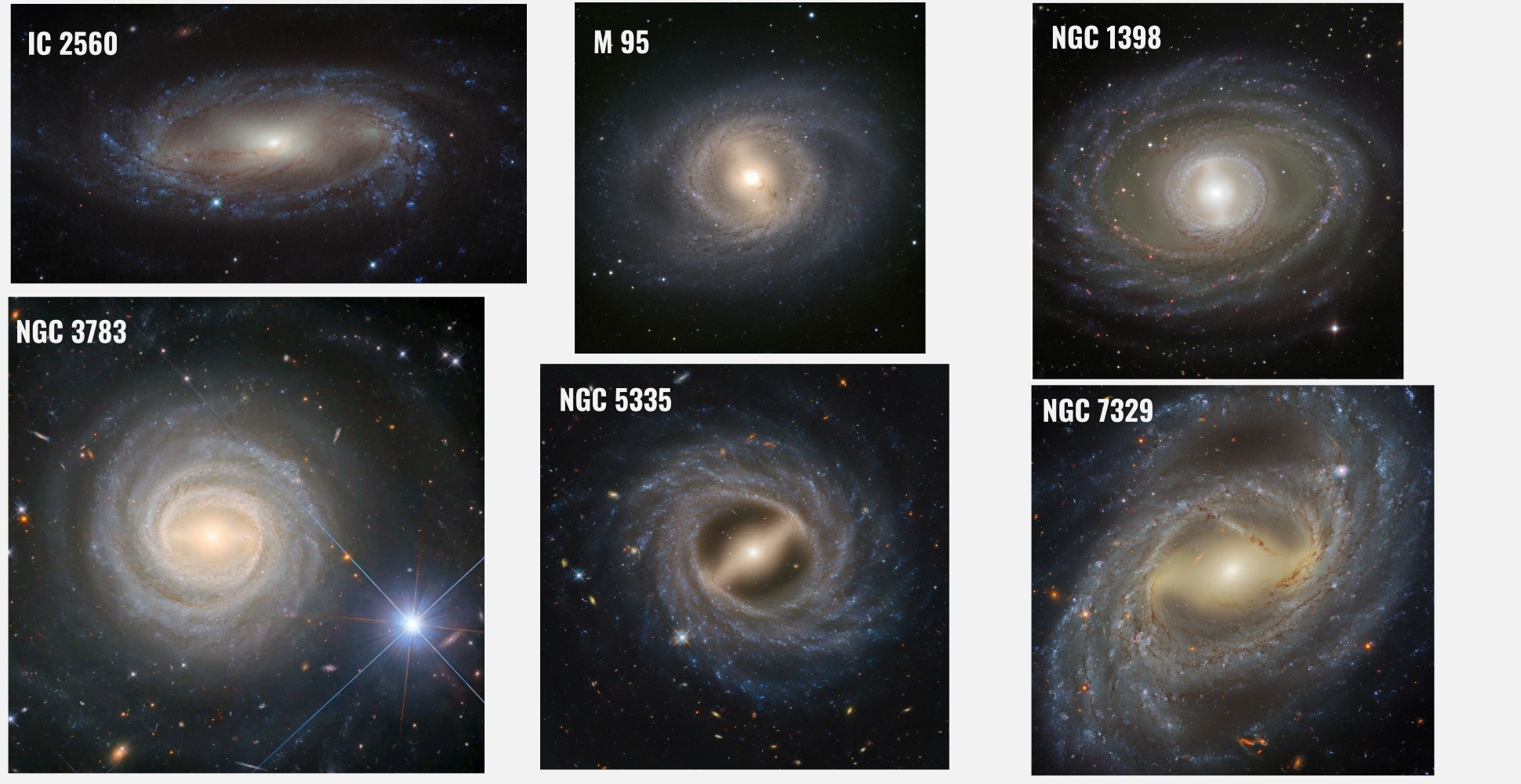

The major focus of the paper, however, was on new evidence from HI4PI about the inner galaxy. Burton concluded that HI4PI shows no distinct interarm gaps in hydrogen concentration in the inner galaxy and

If the inner Galaxy shows no dominant interarm regions, then it shows no spiral arm regions either.

Burton pointed out that there was some evidence against interarm gaps even in the 1960s and he seems to regret not following up.

In contrast, Burton noted that:

the outer Galaxy disk is characterized by quite clearly defined spiral features that extend to large distances from the Galactic center

Burton and Balser conclude:

In their prescient 1952 paper, Oort and Muller note that many spiral galaxies have an “amorphous nucleus” that can be “quite large”. And it turns out that there are many galaxies with such a structure, especially ringed bar galaxies. One of these, Messier 95, is likely familiar to amateur astronomers, but there are many others.

Gaia DR4 and the inner galaxy

My original goal was to briefly summarize what is known about the inner galaxy and then speculate on what Gaia DR4 could add to our knowledge. It turns out, however, that the inner galaxy is a matter of considerable controvery.

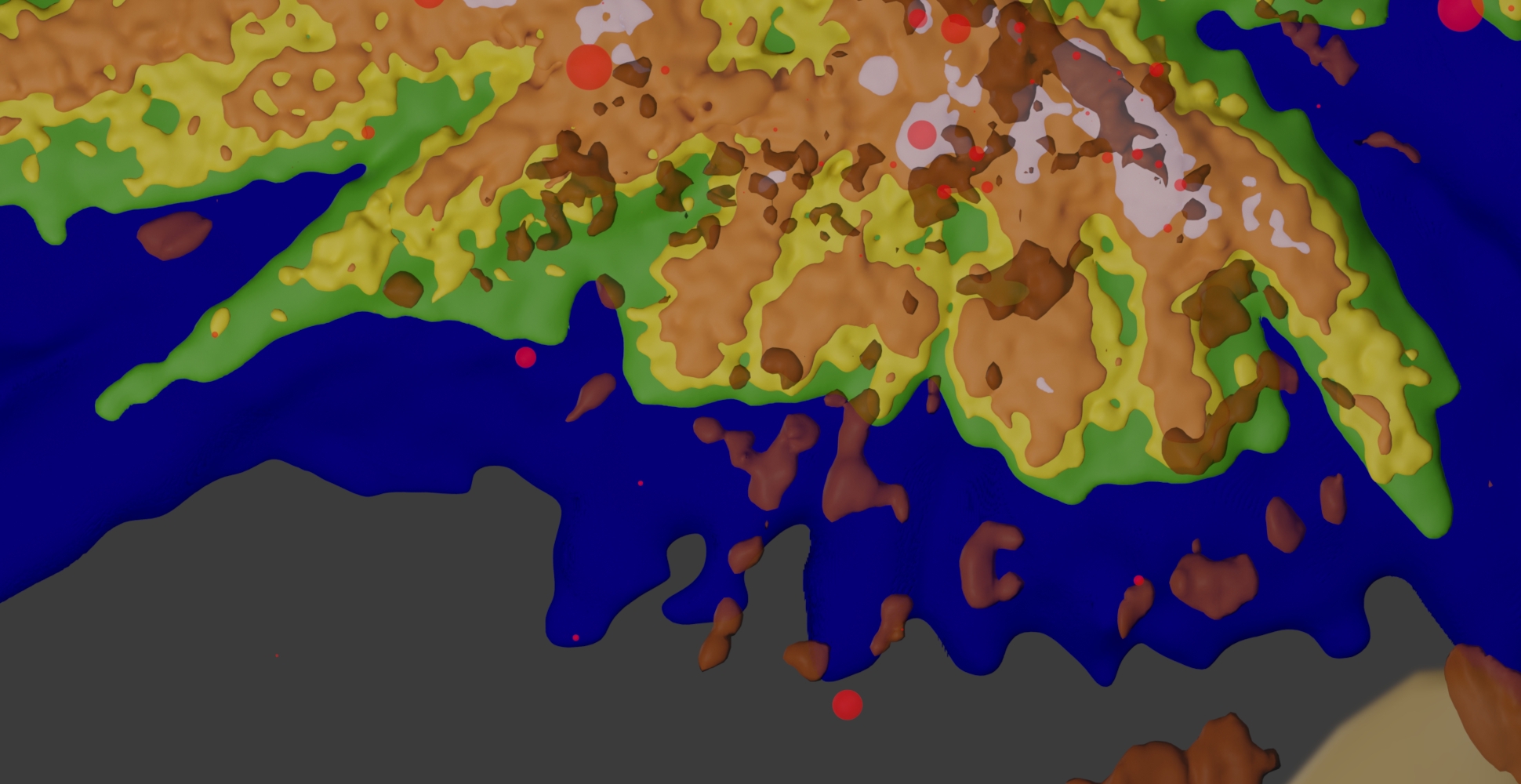

We can see what appears to be a circular boundary for hot star density in the inner galaxy in Gaia DR3.

Gaia DR4 is not going to improve the magnitude limit for the Gaia mission but the parallax errors for the brighter stars are expected to be about half what they are for Gaia DR3. This gives hope that we might be able to create a more detailed version of this image even if we won’t be able to extend it much further.

I am especially interested in the right side of this image as this region is closest to the galactic bar. The Balser and Burton paper states that there are clear spiral structures in the outer galaxy. Many barred spiral galaxies have two major arms that extend outward from the ends of the bar. In Gaia DR4 we may be able to detect in more detail how arms from the outer galaxy interact with the bar and in this analysis the Sagittarius OB associations may yet have a role to play.

I’ll look at Gaia DR4 and the outer galaxy in a separate article.

Related Posts

An improved hot star map

The European Space Agency’s Gaia Mission has revolutionized astronomy in many ways. As just one example, the Gaia Mission has provided the first accurate survey of stars in the galactic plane out to about 5 kpc.

Read moreAcrux board game

There are about 3-5 thousand new board games published every year. A board game designer would need to have a very special game to rise above the crowd.

Read moreCounting down to Gaia DR4

The European Space Agency’s Gaia Mission is the first astronomical mission to create a detailed survey of the Milky Way galaxy far beyond the immediate boundaries of the Local Bubble. The fourth data release, expected in December 2026, is generating much excitement.

Read more